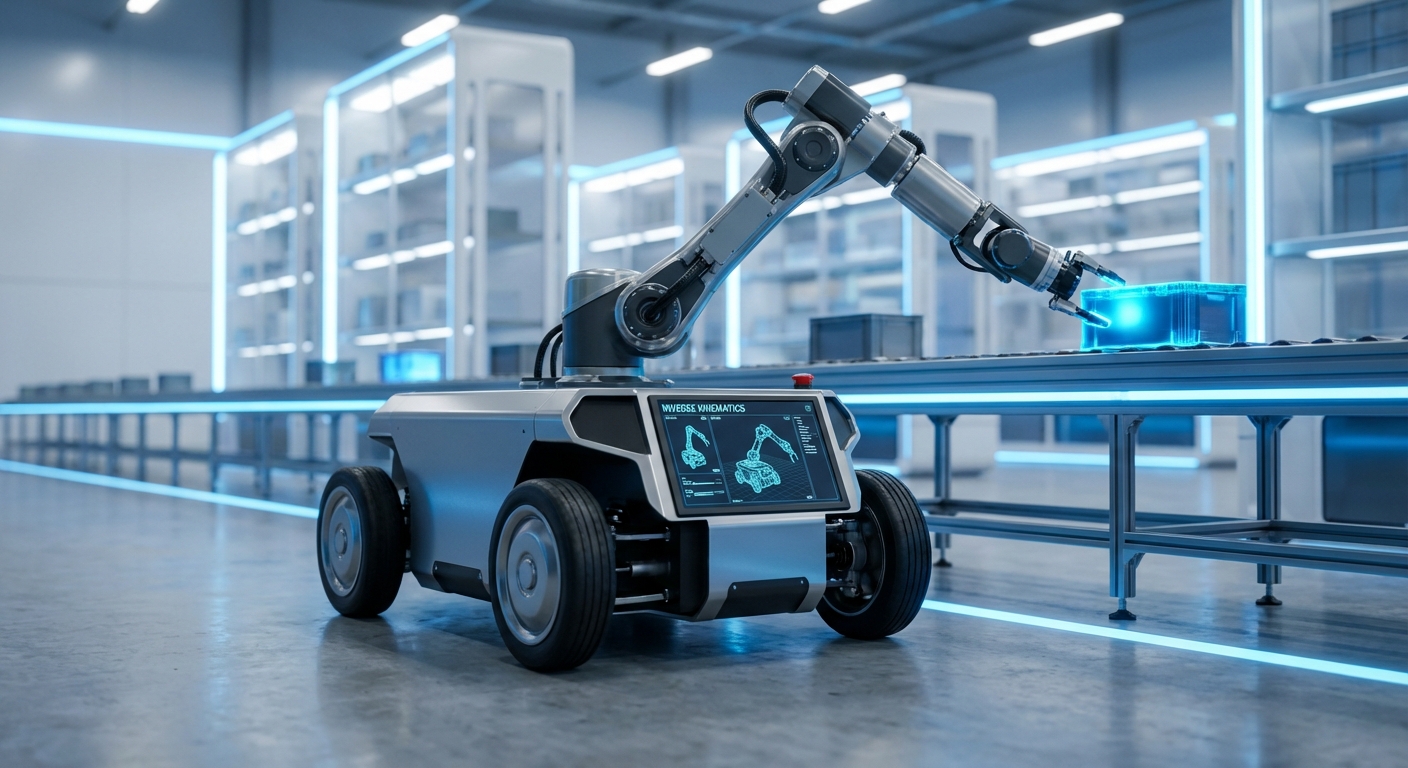

Inverse Kinematics

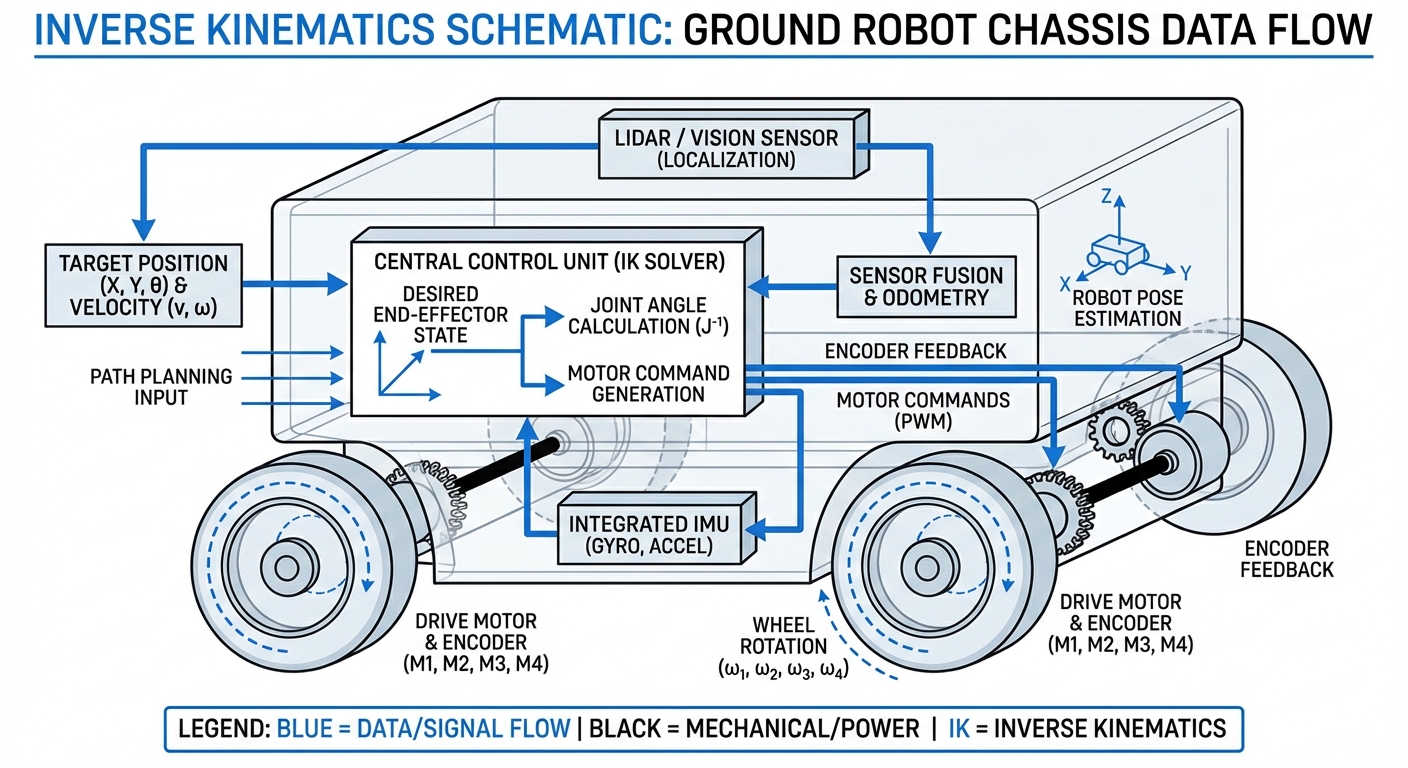

Inverse Kinematics (IK) is the mathematical bridge between a robot's desired path and its physical actuators. It translates high-level motion commands into precise wheel velocities, enabling AGVs to navigate complex environments with sub-millimeter accuracy.

Core Concepts

Task Space

The desired operational area defined by Cartesian coordinates (x, y) and orientation (theta). IK starts here, calculating the required move relative to the global map.

Configuration Space

The vector of joint or wheel variables. For a mobile robot, this represents the individual angular velocities of every motor required to achieve the task.

The Jacobian Matrix

A matrix of partial derivatives relating joint velocities to the end-effector velocity. It is computationally essential for solving IK in real-time navigation.

Holonomic Constraints

Determines if a robot can move in any direction (Omni-wheels) or is limited like a car (Differential Drive). IK equations fundamentally differ based on these physical constraints.

Closed-Loop Control

IK provides the setpoint. PID controllers then monitor sensors (encoders/IMUs) to ensure the physical wheels actually match the calculated velocities.

Singularities

Mathematical edge cases where the robot loses a degree of freedom. Good IK solvers anticipate these states to prevent erratic motion or system locking.

How It Works: The Calculation

Imagine your fleet manager software sends a command: "Move North at 1.0 m/s while rotating 45 degrees." The AGV's computer cannot send this command directly to the motors.

The Inverse Kinematics algorithm intercepts this vector. Using the robot's physical geometry—specifically the wheelbase (distance between wheels) and track width—it calculates the exact RPM required for the left wheel versus the right wheel.

For a standard differential drive robot, to turn right, the algorithm dictates that the left wheel must spin faster than the right wheel. For Mecanum-wheeled robots, the math is more complex, involving vector summation to achieve strafing motion without rotation.

This calculation happens hundreds of times per second, adjusting for micro-corrections in trajectory to keep the robot perfectly on its virtual path.

Real-World Applications

Precision Warehouse Docking

AGVs use inverse kinematics to align charging ports or conveyor belts with millimeter-level tolerance. IK allows the robot to perform micro-adjustments in approach angle to ensure a perfect latch every time.

Dynamic Obstacle Avoidance

In busy factories, paths change instantly. IK algorithms rapidly translate new path plans from the navigation stack into immediate motor reactions, allowing smooth swerving around humans or forklifts.

Medical & Hospital Transport

Transporting sensitive bio-samples requires jerk-free motion. Advanced IK profiles smooth out acceleration curves, ensuring liquids remain stable even during complex turning maneuvers.

Omnidirectional Assembly

For heavy-load manufacturing platforms using mecanum wheels, IK handles the complex vector math required to strafe sideways or spin in place, allowing assembly of large components in tight cells.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between Forward and Inverse Kinematics?

Forward kinematics calculates the robot's position in the world based on known wheel rotations (odometry). Inverse kinematics does the reverse: it takes a desired target position or velocity and calculates the necessary wheel rotations to get there.

Why is Inverse Kinematics difficult for non-holonomic robots?

Non-holonomic robots (like cars or standard differential drive AGVs) cannot move sideways instantaneously. The IK solver must account for these constraints, often requiring path planning curves (like Bezier or Dubins paths) rather than straight-line vectors to reach a lateral target.

How does wheel slippage affect Inverse Kinematics calculations?

IK assumes perfect traction, which rarely exists in reality. When wheels slip, the calculated velocity results in incorrect motion. To combat this, robust systems use closed-loop feedback with IMUs or LiDAR (SLAM) to correct errors between the IK command and actual robot pose.

What is the computational load of IK on an embedded MCU?

For mobile bases, the computational load is generally low and runs easily on standard microcontrollers like STM32 or ESP32. However, for 6-axis robotic arms mounted on AGVs, the iterative IK solvers (like Newton-Raphson) are CPU-intensive and often require dedicated industrial PCs.

How does a mecanum wheel AGV differ in IK mathematics?

Mecanum robots have three degrees of freedom (x, y, rotation) compared to two for differential drives. The IK matrix is a 4x3 matrix that sums force vectors, meaning the math must balance opposing wheel forces to create sideways motion without rotation.

Does changing wheel diameter require re-coding the IK?

Yes, absolutely. The wheel radius is a fundamental constant in the velocity equation ($v = \omega \times r$). If tires wear down or are replaced with different sizes, the parameters must be updated, or the robot will consistently under- or overshoot its target.

What happens at a singularity point?

A singularity occurs when the Jacobian matrix loses rank, meaning there are infinite solutions or no solution for a movement (e.g., a fully extended arm). For mobile bases, this is rare, but can happen in steering linkage designs where wheels align in a way that locks motion.

Can IK handle uneven terrain?

Standard planar IK assumes a flat surface. On uneven terrain, the effective contact point of the wheel changes, introducing errors. Advanced AGVs use 3D kinematic models and suspension sensors to dynamically adjust the IK calculations for slopes and bumps.

Is ROS (Robot Operating System) required for IK?

No, IK is purely mathematical and can be implemented in C++, Python, or PLC logic. However, ROS provides standard libraries (like the Navigation Stack) that abstract the IK complexities, making implementation significantly faster for developers.

How does "Ackermann Steering" IK differ from Differential Drive?

Ackermann steering (car-like) couples the angle of the front wheels with the speed of the rear wheels. The IK is more restrictive regarding minimum turning radius, whereas differential drive robots can rotate in place ($r=0$), simplifying the math for tight maneuvers.

What role do encoders play in IK?

Encoders verify the output of the IK. The IK calculates the *required* speed, the motor driver attempts to achieve it, and the encoders measure the *actual* speed. The PID controller minimizes the difference between the IK setpoint and the encoder feedback.

How accurate is IK for long-distance navigation?

IK alone is poor for long distances due to "dead reckoning" drift (accumulating small errors). It is meant for local motor control. Long-distance accuracy relies on global localization (Lidar/QR codes) resetting the position estimate that feeds into the IK loop.